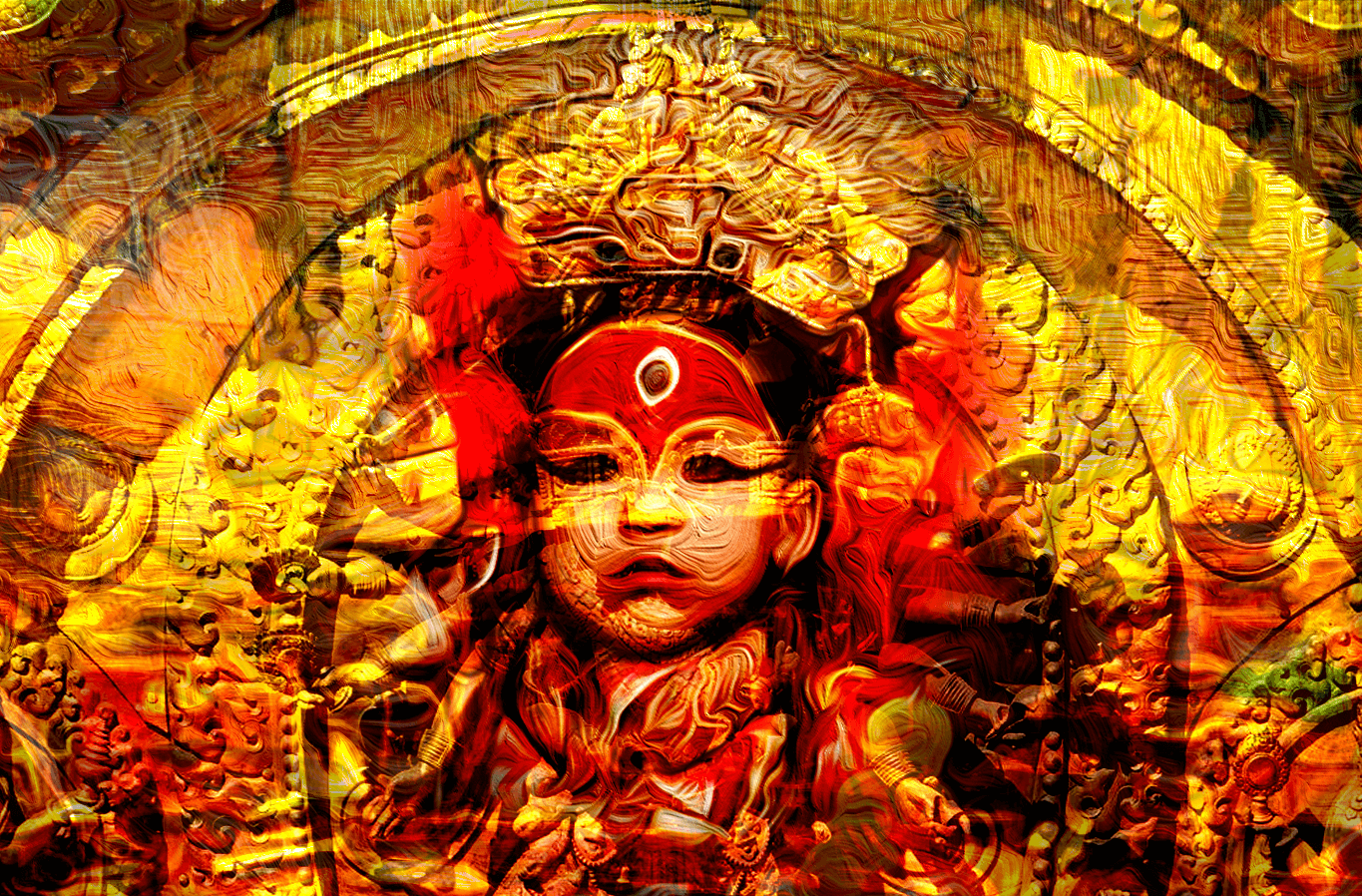

Kumari of Kathmandu

Kumari, a young girl revered as a goddess by the Newars, the indigenous community of the Kathmandu Valley, is the subject of a sensational and controversial tradition.

When a Kumari suffers from a serious illness or any form of bleeding, she becomes disqualified to continue her duties, and a process to appoint a new goddess begins.

Shortly after, her life transforms from that of a goddess to that of a normal human, which could be a traumatic experience.

The cycle of selecting a Kumari begins with a girl who is at least two years old and is assumed to possess all 32 “perfections”. It involves a testing process, which is a peculiar tradition of turning a human into a god governed by patriarchy.

The worship of females can be traced back to the Stone Age, where the feminine figures, known as Venuses, may have been used for religious purposes or statues of goddesses. What is certain is that the worship of females specifically virgin worship is an ancient practice in various cultures.

The Kumari-puja, involving virgin worship, dates back to at least the late Vedic period. The earliest reference can be found in the Taittiriya Aryanyaka, around the 6th-7th century BCE.

Nepali chronicles (Vamshawalis) date the tradition to at least the 6th century CE, discussing the feasting of Kumaris during the festival when the chariot carrying images of Mahadeva, a Hindu deity, is paraded in the streets.

To gain a deeper understanding of the practice of Kumari worship, we can trace its culture within Kathmandu Valley to at least 1024-40 CE, during the reign of King Lakshmikamadeva of Kathmandu.

Historical literature reveals the daughter of the Shakya caste was worshipped as Kumari, who resided in a monastery called Lakshmi-barman, located near the palace in Patan, a city within the Kathmandu Valley.

This narrative diverges from the widely known story associated with the Malla kings of either Patan or Kathmandu. According to this story, one the these kings engaged in a dice game called tripasa with the goddess Taleju which unfortunately led to an inappropriate action. After the incident, the goddess stopped coming in her divine form and ordered the king to select a Shakya girl who would host her manifestation.

The history of Taleju in Kathmandu only starts with King Hari Singh Deva of the Karnataka dynasty, who arrived in Nepal two centuries after the formal recording of the Kumari tradition in Kathmandu. The Historical literature suggests that Taleju Bhavani was originally brought from South India in Tuljapur, which is located in present-day Maharastra.

Throughout history, rulers have often used religion as a medium to legitimatize their authority. The Malla kings, originally hailing from South India, connected the pre-existing Kumari tradition with their lineage deity as a strategy to enhance their legitimacy.

The tradition of respecting Kumari was inherited by the last dynasty of Nepal, the Shah dynasty. This was a political statement showing the aspiration of the first king of the last dynasty as a preserver of the culture and not a colonial master. The first action taken by the Shah monarch after invading Kathmandu receive prasad from the Kumari.

At present, the head of the state via the President in the Secular Republic of Nepal continues the process of receiving prasad from the Kumari. Presidents continue the age-old tradition of legitimizing their position.

The Kumari tradition predates the Malla era, which raises questions about whether the Kumari can be considered the lineage deity of Malla kings.

In the present day, there are ten Kumaris, while in 1975, Michael Allen mentioned that there were six Kumaris from the Shakya caste, another five from the Vajracharya caste, and two from the Jyapu community.

While the Shakya girl, even though belonging to the Buddhist community, is worshipped in the form of the Hindu goddess Taleju, the Vajracharya Kumari is associated with Buddhism and Tantric tradition and is revered as a Vajradevi.

There are also instances when the Kumari of Bhaktapur, on June 3, 2007, traveled to America to attend the screening of the movie “Living Goddess” at Silverdocs. During this period, she was temporarily displaced from her position but later reinstated after a cleansing ceremony was conducted.

It is evident that the international media, at times, becomes captivated by specific Kumaris, often emphasizing the political significance rather than approaching the subject from a sociological and cultural perspective.

An opportunity exists to explore the lesser-known Kumaris, who operate without the same restrictions and may face the risk of fading and ceasing to exist in the near future.

Studying these lesser-known Kumaris can reveal the authentic narratives of Nepal’s living goddesses, who aren’t embroiled in controversies related to child rights violations. They lead relatively normal lives but remain revered by devotees, embodying a different aspect of this tradition.

Author

Kripendra Amatya, Researcher, Nepa~laya Productions

Editor

Dana Moyal Kolevzon, Director of International Relations, Nepa~laya Productions

Published Date

January 1, 1970