Nepal’s Stolen Artifacts

In South Asia, the punishment for theft was subject to caste as defined by Manusmriti. Much of the Indo-Aryan literature became the foundation of the Nepalese legal system.

The major historical law manual in Nepal is Manav Nyaya Shastra codified by King Jayasthiti Malla of Nepal. As per Manav Nyaya Shastra, the theft of gold, and gems, belonging to the god Brahman, and the king, was considered a severe crime.

The punishment for stealing gold, silver, and similar valuable items, would be death. Nepal’s interaction with the Western world in the 1950s created a high demand for exotic Nepali artifacts.

The first historical evidence of a religious object stolen from Nepal was recorded in 1765, when the Narayan statue disappeared from the Bhagwati temple in Hanuman Dhoka Palace, in Kathmandu valley.

The earliest pieces of evidence of people trying to sell statues to the West can be found in An Account of The Kingdom of Nepal. The King of Kathmandu, Jay Prakash Malla had excavated an underground vault when several exclusive small figures were stolen by his workers. One of those workers, offered Father Giuseppe to purchase a stolen figure.

During the early Shah period, the Shah rulers were known to be extremely wary of European Colonialism, and as a result, they maintained limited contact with Europeans which continued until the mid-20th century.

After the 1950s, Nepal started opening up to foreigners, and artifact thefts by foreigners became prevalent.

In 1956, Nepal commenced the Ancient Monument Preservation Act 2013.

The Act declared that stealing any ancient artifact would result in severe fines and imprisonment, but this didn’t deter smugglers. And by the 1980s over 500 idols were stolen.

The Local Administration Act of 1971 handed legal responsibility of conducting inventory and promoting local heritage and culture to local governments and Chief District Officers.

Similarly, the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibition and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property was ratified by Nepal in 1976. The Convention paved the way for the recovery of stolen or illegally exported cultural property that was transferred from Nepal.

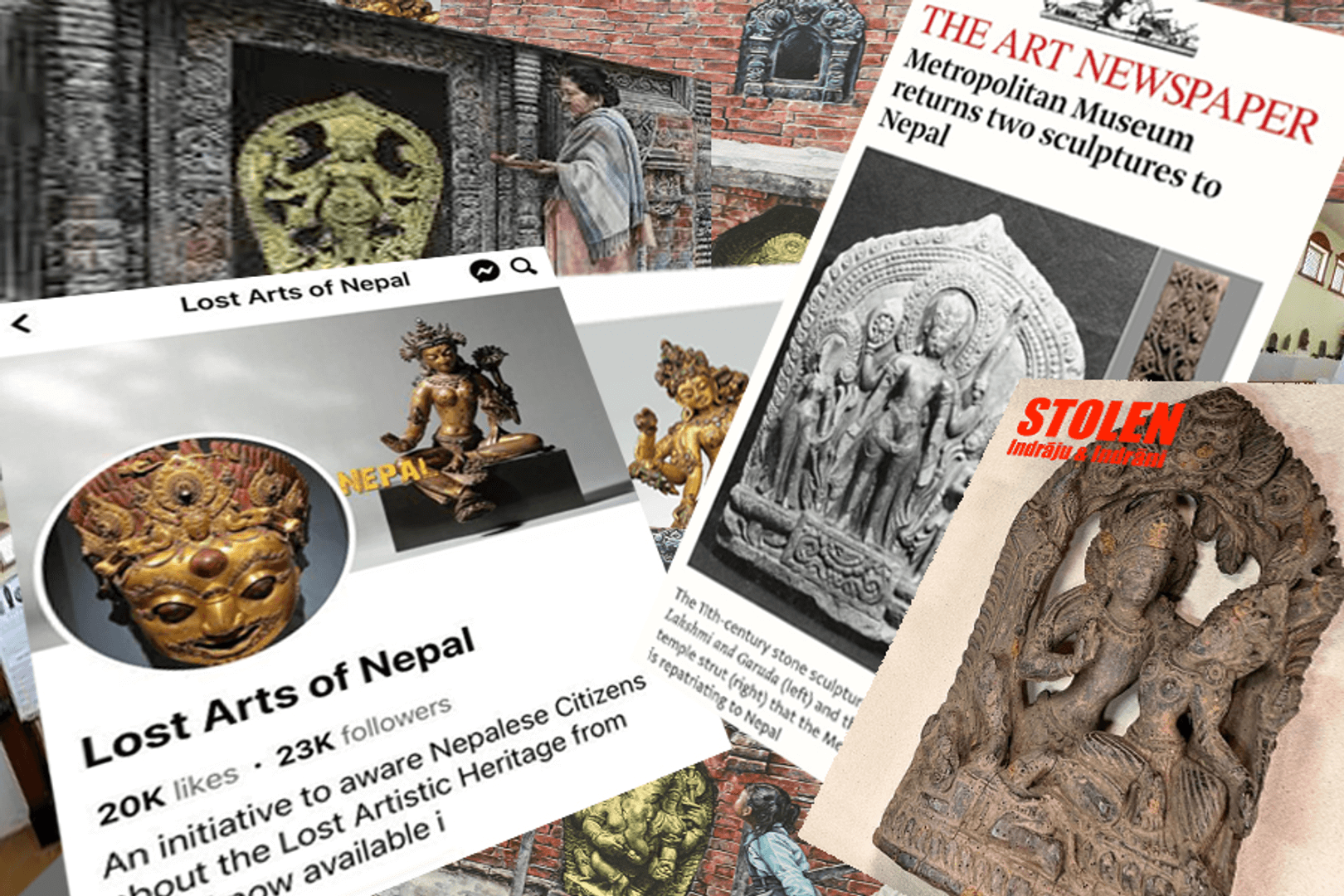

In the 1980s and 90s, Lain Singh Bangdel and German citizen Jurgen Schick photographed idols and documented the deities, which helped provide proof when retrieving the stolen artifacts around the world.

In 1994, many idols were returned to Nepal by the US and were kept in Nepal’s National Museum in Chhauni. Similarly, in 1999 the German government returned a 12th century-old Uma Maheshwor stolen from Dhulikhel, and in 2002 Austria returned the statue of Dipankar Buddha.

There has also been the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign to retrieve the stolen artifacts. This has spread awareness to bring the heritage pieces back to Nepal.

In total 96 precious artifacts were repatriated to Nepal after decades by June 2023.

The final question remains how did the statues get stolen from Nepal, and if there were high-level connections in this crime?

Alsdorf Galleries was opened by the Art Institute of Chicago. It displayed a Taleju necklace in its galleries, but then a Nepali academic spotted it, and an effort grew to retrieve it. The Art Institute sought to find a connection between the Nepali royal family's involvement to continue holding the piece of jewelry.

By 1970, the Panchayat government ordered the necklace to be moved to the Hanuman Dhoka Museum and have it guarded by the Royal Nepal Army, but then in 1976, it disappeared.

One Royal family member who continued to be surrounded by controversy was Dhirendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev. On August 8, 1972, the Supreme Court had a hearing on the artifacts procured by Prince Dhirendra. The court ruled that the recovered idols could not be returned.

The audacity of crime in Panchayat was so high that in 1983 thieves tried to steal the statue of Bhupatindra Malla in broad daylight using a crane inside a major city within Kathmandu Valley. The theft was stopped by angry locals and the police. People naturally became suspicious of any possible connection between the crime with the royal family.

The subject of Nepal’s stolen artifacts is multi-faceted, and there is an opportunity to produce an investigative documentary that could perhaps reveal even more than what we know now.

Author

Kripendra Amatya, Researcher, Nepa~laya Productions

Editor

Dana Moyal Kolevzon, Director of International Relations, Nepa~laya Productions

Published Date

January 1, 1970